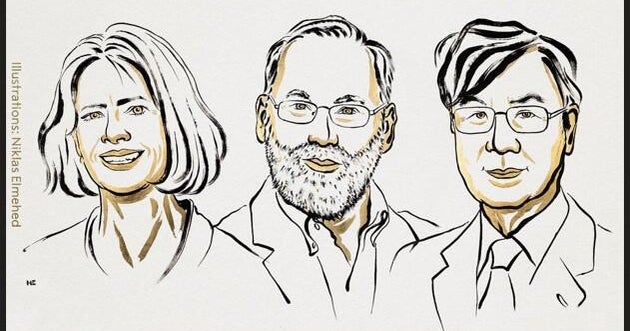

Stockholm — Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Dr. Shimon Sakaguchi won the Nobel Prize in medicine on Monday for their discoveries concerning peripheral immune tolerance.

Brunkow, 64, is a senior program manager at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle. Ramsdell, 64, is a scientific adviser for Sonoma Biotherapeutics in San Francisco. Sakaguchi, 74, is a distinguished professor at the Immunology Frontier Research Center at Osaka University in Japan.

Brunkow got the news of her prize from an AP photographer who came to her home in the early hours of the morning.

She said she had ignored the earlier call from the Nobel committee. “My phone rang and I saw a number from Sweden and thought: ‘That’s just, that’s spam of some sort.'”

“When I told Mary she won, she said, ‘don’t be ridiculous,'” said her husband, Ross Colquhoun.

“It was a nice surprise,” Sakaguchi told a news conference from the University of Osaka in western Japan. “I hope researches into the area will further progress so that our findings can be used in treatment, and I hope we can contribute to that as well.”

The immune system has many overlapping systems to detect and fight bacteria, viruses and other bad actors. Key immune warriors such as T cells get trained on how to spot bad actors. If some instead go awry in a way that might trigger autoimmune diseases, they’re supposed to be eliminated in the thymus – a process called central tolerance.

The Nobel winners unraveled an additional way the body keeps the system in check.

The Nobel Committee said it started with Sakaguchi’s discovery in 1995 of a previously unknown T cell subtype now known as regulatory T cells or T-regs. Then in 2001, Brunkow and Ramsdell discovered a culprit mutation in a gene named Foxp3, a gene that also plays a role in a rare human autoimmune disease.

The Nobel Committee said two years later, Sakaguchi linked the discoveries to show that the Foxp3 gene controls the development of those T-regs – which in turn act as a security guard to find and curb other forms of T cells that overreact.

Brunkow said she and Ramsdell were working together at a small biotech company and they were investigating why a particular strain of mice had an over-active immune system. They had to work with brand new techniques to find the mouse gene behind the problem — but quickly realized it could be a major player in human health, too.

“From a DNA level, it was a really small alteration that caused this massive change to how the immune system works.”

The work opened a new field of immunology, said Karolinska Institute rheumatology professor Marie Wahren-Herlenius. Researchers around the world now are working to use regulatory T cells to develop treatments for autoimmune diseases and cancer.

“Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” said Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee.

The award is the first of the 2025 Nobel Prize announcements and was announced by a panel at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Nobel announcements continue with the physics prize on Tuesday, chemistry on Wednesday and literature on Thursday. The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced Friday and the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics Oct. 13.

The award ceremony will be held Dec. 10, the anniversary of the death of Alfred Nobel, who founded the prizes. Nobel was a wealthy Swedish industrialist and the inventor of dynamite. He died in 1896.

The trio will share the prize money of 11 million Swedish kronor (nearly $1.2 million).